The Mexican War of Independence stands as a pivotal chapter in the history of Mexico, marking the culmination of centuries of colonial rule and the birth of a new nation.

Spanning over a decade, this tumultuous period was characterized by courageous uprisings, strategic alliances, and the unwavering determination of countless individuals to break free from Spanish dominance.

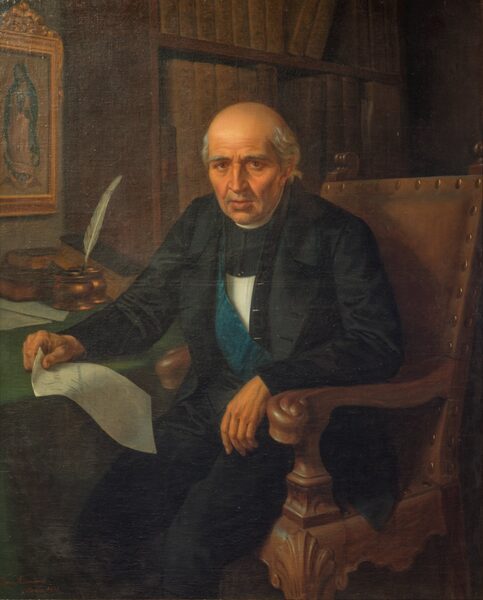

In this comprehensive article, we delve into the intricacies of the Mexican War of Independence, tracing its origins from the fervent cries of Miguel Hidalgo in the Grito de Dolores to the triumphant declaration of Mexico’s sovereignty in the Treaty of Córdoba.

We explore the pivotal moments, key figures, and enduring legacies that have shaped Mexico’s national identity and continue to resonate to this day.

| Event | Description |

|---|---|

| Grito de Dolores (1810) | Miguel Hidalgo issues the Grito de Dolores, calling for rebellion against Spanish rule, marking the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence. |

| Hidalgo’s Rebellion (1810-1811) | Hidalgo leads a mixed army of mestizos and indigenous people, capturing key cities, but is eventually defeated by Spanish forces. Hidalgo is captured and executed in 1811. |

| Morelos’ Leadership (1811-1815) | José María Morelos takes over leadership of the independence movement, leading successful military campaigns and establishing a congress to draft a constitution. |

| Execution of Morelos (1815) | Morelos is captured by Spanish forces and executed, dealing a blow to the independence movement. |

| Guerrero and Iturbide (1815-1821) | Independence movement persists under leaders like Vicente Guerrero and Agustín de Iturbide. Iturbide declares the Plan of Iguala, which calls for Mexico’s independence and unity among Mexicans. |

| Plan of Iguala and Treaty of Córdoba (1821) | The Plan of Iguala gains support, and the Treaty of Córdoba is signed, officially recognizing Mexican independence. |

| End of Spanish Rule (1821) | The Army of the Three Guarantees, led by Iturbide, enters Mexico City, ending Spanish colonial rule. Iturbide is declared emperor, but his reign is short-lived. |

| Declaration of the Republic (1823) | Iturbide abdicates in 1823, and Mexico is declared a republic. A constitution is drafted. |

| Consolidation of Independence (1823-1824) | Mexico stabilizes under a republican government, facing internal strife and external threats following independence. |

Timeline of the Mexican War of Independence

Grito de Dolores (1810): Miguel Hidalgo issues the Grito de Dolores, marking the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence

Miguel Hidalgo, a Catholic priest in the town of Dolores, issues the Grito de Dolores on September 16, 1810.

This passionate call to arms rallied Mexicans against Spanish colonial rule. Hidalgo’s cry for independence sparked a widespread uprising that quickly spread through central Mexico. The Grito de Dolores is now celebrated annually as Mexico’s Independence Day.

Hidalgo’s Rebellion (1810-1811): Hidalgo leads a mixed army but is eventually defeated and executed

Following the Grito de Dolores, Miguel Hidalgo led a diverse army composed of indigenous peasants, mestizos, and some creole intellectuals. They captured key cities such as Guanajuato and Valladolid (modern-day Morelia), but their lack of military discipline and strategy led to setbacks.

Also Read: Mexican Revolution Facts

Despite initial successes, Hidalgo’s forces were defeated by royalist troops at the Battle of Calderón Bridge in January 1811. Hidalgo was eventually captured, defrocked, and executed by firing squad in July 1811. His execution did not end the rebellion, but it significantly weakened the insurgent forces.

Morelos’ Leadership (1811-1815): José María Morelos leads successful campaigns and establishes a congress

After Hidalgo’s death, leadership of the independence movement passed to José María Morelos, a former student of Hidalgo’s.

Morelos proved to be a skilled military strategist and an effective leader. He reorganized the insurgent forces, adopting guerrilla tactics to harass Spanish troops and capture important towns.

Also Read: Mexico History Timeline

Morelos also convened the Congress of Chilpancingo in 1813, where he presented the “Sentiments of the Nation,” a document that outlined principles for an independent Mexico and proposed a democratic government.

Under Morelos’ leadership, the independence movement gained momentum, with notable victories in places like Acapulco and Cuautla. However, Morelos faced challenges from both internal dissent and external military pressure.

Despite his efforts, Morelos was captured by Spanish royalist forces in 1815 and subsequently executed. His death dealt a significant blow to the independence cause, but his legacy continued to inspire future leaders in the struggle for Mexican independence.

Execution of Morelos (1815): Morelos is captured and executed by Spanish forces

After the capture of José María Morelos, he was subjected to a trial by the Spanish authorities. Despite his efforts to defend himself and his cause, Morelos was ultimately found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

His execution took place on December 22, 1815, in the town of San Cristóbal Ecatepec. Morelos’ death dealt a significant blow to the independence movement, as he was not only a skilled military leader but also a visionary statesman who had laid out plans for a democratic and independent Mexico.

However, despite his execution, the spirit of independence persisted among Mexicans, and the struggle continued.

Guerrero and Iturbide (1815-1821): Leaders like Vicente Guerrero and Agustín de Iturbide persist in the independence movement

Following Morelos’ death, various leaders emerged to carry on the fight for independence. One of the most notable figures during this period was Vicente Guerrero, a mestizo leader who continued to lead guerrilla warfare against the Spanish forces.

Another significant figure was Agustín de Iturbide, a former royalist officer who switched sides and joined the independence movement. Iturbide’s involvement proved pivotal, as he eventually formulated the Plan of Iguala in 1821.

This plan called for Mexican independence, the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, and equality between Mexicans of European and indigenous descent.

Iturbide’s leadership, along with the support of Guerrero and others, helped to unite various factions within the independence movement.

Plan of Iguala and Treaty of Córdoba (1821): The Plan of Iguala gains support, leading to the Treaty of Córdoba and official recognition of Mexican independence

The Plan of Iguala, also known as the Plan of the Three Guarantees, was proclaimed by Agustín de Iturbide on February 24, 1821. This plan outlined three primary goals: independence, the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, and the equality of all inhabitants of Mexico.

The plan gained widespread support among various factions, including royalists and insurgents, due to its inclusive nature. Subsequently, representatives of Iturbide and the Spanish crown negotiated the Treaty of Córdoba, which was signed on August 24, 1821.

This treaty officially recognized Mexico’s independence from Spain and marked the end of three centuries of colonial rule. The signing of the Treaty of Córdoba effectively brought an end to the Mexican War of Independence and laid the groundwork for the establishment of a new nation.

End of Spanish Rule (1821): Iturbide’s Army of the Three Guarantees enters Mexico City, ending Spanish colonial rule

Following the signing of the Treaty of Córdoba, Agustín de Iturbide’s Army of the Three Guarantees entered Mexico City on September 27, 1821. This event marked the culmination of the Mexican War of Independence and effectively ended Spanish colonial rule in Mexico.

Iturbide was hailed as a hero, and celebrations erupted throughout the country as Mexico embarked on a new era as an independent nation.

Declaration of the Republic (1823): Iturbide abdicates, and Mexico is declared a republic with a drafted constitution

Despite Iturbide’s initial popularity, his rule as emperor faced opposition from various political factions. In 1823, faced with growing discontent and the threat of civil war, Iturbide abdicated the throne and went into exile. With Iturbide’s departure, Mexico transitioned to a republican form of government.

On October 4, 1824, the Mexican Congress adopted the Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States, establishing Mexico as a federal republic with a division of powers between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

This marked the formal declaration of the Republic of Mexico and laid the foundation for the country’s democratic governance.

Consolidation of Independence (1823-1824): Mexico stabilizes under a republican government, facing internal and external challenges

The period following the declaration of the republic was characterized by efforts to consolidate Mexico’s independence and establish stability. However, the fledgling republic faced numerous challenges, including internal divisions, regional conflicts, and external threats.

Political factions vied for power, leading to periods of instability and conflict. Additionally, Mexico’s vast territorial expanse posed challenges to effective governance.

Despite these challenges, efforts were made to strengthen the institutions of the new republic and promote national unity. This period laid the groundwork for the development of Mexico as a sovereign and independent nation.