The Declaration of Independence is a foundational document in American history, marking the formal separation of the Thirteen Colonies from Great Britain.

Its creation and adoption in 1776 were pivotal events in the American Revolutionary War and the establishment of the United States.

The Declaration outlined the colonies’ grievances against the British Crown and articulated key principles of individual rights and self-governance, profoundly influencing democratic movements worldwide.

This timeline delves into the significant events surrounding its drafting, debate, adoption, and aftermath, showcasing the critical steps that led to the birth of a new nation committed to liberty and equality.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| June 11, 1776 | The Continental Congress appoints the “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of independence. The committee includes Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. |

| June 28, 1776 | The committee presents its draft of the declaration to the Continental Congress. |

| July 1-4, 1776 | The Congress debates and revises the draft of the Declaration of Independence. |

| July 2, 1776 | The Continental Congress votes in favor of independence. |

| July 4, 1776 | The final version of the Declaration of Independence is adopted by the Continental Congress. This day becomes known as Independence Day in the United States. |

| July 5-9, 1776 | The Declaration of Independence is printed and publicly disseminated. |

| August 2, 1776 | The engrossed copy of the Declaration is signed by most of the congressional delegates. |

Timeline of Declaration of Independence

June 11, 1776 – Appointment of the Committee of Five

The Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, recognizes the need for a formal declaration to announce and justify the decision to break away from British rule.

They appoint the “Committee of Five” to undertake this task. This committee is composed of five members with diverse backgrounds and talents:

- Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, a young but eloquent writer and lawyer known for his advocacy of colonial rights.

- John Adams of Massachusetts, a leading figure in the push for independence and a skilled debater.

- Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, the oldest member of the committee and highly respected for his wisdom, diplomatic skills, and scientific accomplishments.

- Roger Sherman of Connecticut, known for his ability to mediate disputes and his experience in legal and governmental matters.

- Robert R. Livingston of New York, a lawyer and diplomat. Livingston would later help negotiate the Louisiana Purchase.

The committee’s primary task was to draft a document that would explain the reasons for independence, rally support among the colonists, and seek assistance from foreign nations.

June 28, 1776 – Drafting of the Declaration

Thomas Jefferson is chosen to write the first draft due to his eloquent writing style and strong stance on independence. He works on the draft in his lodgings in Philadelphia.

Jefferson draws upon his own draft of the Virginia Constitution, as well as other existing documents like the Virginia Declaration of Rights. His draft includes philosophical and political ideas about natural rights and the social contract, influenced by Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke.

After completing the draft, Jefferson presents it to Adams and Franklin, who make revisions. The most significant change is the removal of a passage indicting King George III for the slave trade, a contentious issue among the colonies.

July 1-4, 1776 – Congressional Debate and Revision

The draft is presented to the Continental Congress on June 28 but is not immediately discussed as Congress is still debating whether to officially declare independence. The debate is intense, reflecting the gravity of severing ties with Britain.

On July 1, a vote on independence is postponed as some delegates, like those from Pennsylvania and South Carolina, are hesitant. However, following intense discussions and lobbying, including an impassioned speech by John Adams, the Congress is swayed.

The Congress then turns to Jefferson’s draft. Over the next two days, the Congress makes numerous changes, shortening the text by about a fourth. While Jefferson is disheartened by some of the alterations, the revisions are essential to gain the support of all the delegates.

On July 4, the Congress finalizes the text of the Declaration of Independence, officially explaining and justifying the decision to break away from British rule. This moment marks a turning point in the history of the American colonies, setting the stage for the formation of a new, independent nation.

July 2, 1776 – Congress Votes for Independence

This day marks a pivotal moment in American history. The Continental Congress, after much debate, votes in favor of Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence.

This resolution, initially presented on June 7, declares, “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, Free and Independent States.” The vote for independence is nearly unanimous, with 12 of the 13 colonies voting in favor (New York abstains, but later votes affirmatively).

This decision officially sets the stage for the adoption of a formal Declaration of Independence. John Adams, in a famous letter to his wife, predicted that July 2 would be celebrated by future generations as the great anniversary festival.

July 4, 1776 – Adoption of the Declaration of Independence

Two days after voting for independence, the Continental Congress formally adopts the Declaration of Independence.

This document, primarily written by Thomas Jefferson and revised by the Congress, declares the colonies to be free and independent states, no longer subject to British rule. It outlines the philosophical and practical reasons for separation, including a list of grievances against King George III.

The adoption of the Declaration is a revolutionary act, signifying the birth of a new nation – the United States of America. July 4th becomes known as Independence Day, a national holiday celebrated in the United States.

July 5-9, 1776 – Printing and Public Dissemination

Immediately following its adoption, the Declaration of Independence is printed by John Dunlap, a printer in Philadelphia. These first printed copies, known as the Dunlap Broadsides, are quickly distributed throughout the 13 colonies.

They are read aloud in public squares, to colonial troops, and in churches, spreading the news of independence far and wide. This dissemination plays a crucial role in rallying support among the colonists and informing them of the Congress’s decision.

The widespread distribution of the declaration also serves to unite the disparate colonies under the common cause of independence.

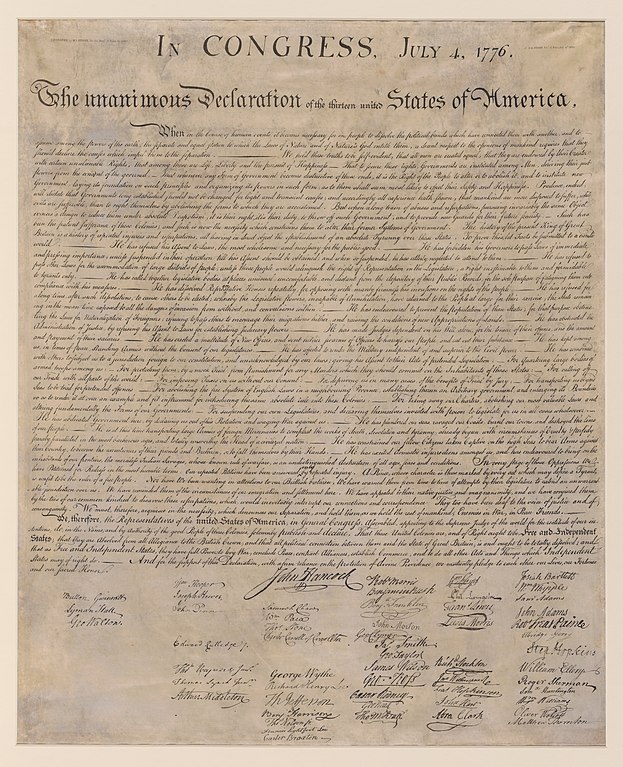

August 2, 1776 – Signing of the Engrossed Copy

While the Declaration is adopted and printed in July, the actual signing of the document by members of the Continental Congress takes place on August 2, 1776.

This is done on an engrossed (officially inscribed) copy of the Declaration. Contrary to popular belief, not all delegates sign on this day.

Signatures are added later as delegates return to Philadelphia or are newly appointed to the Congress. The signing is not a single dramatic moment but a process that continues into the fall of 1776.

The most notable signature is that of John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress, whose large and flamboyant signature becomes iconic. The signed Declaration becomes a powerful symbol of the colonies’ commitment to the principles of liberty and self-governance.