During the colonial period, spanning roughly from the early 17th century to the late 18th century, European powers, particularly Britain, established settlements and colonies in North America. These colonies played a pivotal role in shaping the future United States of America.

The early colonies faced numerous challenges, including interactions and conflicts with Native American tribes, struggles for survival, and the establishment of their own forms of government.

Over time, tensions between the colonies and the British crown grew, leading to a series of events that eventually culminated in the American Revolution and the birth of a new nation.

The colonial era was marked by diverse religious, cultural, and economic influences, setting the stage for the formation of a unique American identity and the principles that would shape the country’s future.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1607 | Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America, is founded in Virginia. |

| 1620 | The Pilgrims establish Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts. |

| 1630 | The Massachusetts Bay Colony is established by Puritan settlers, with Boston as its capital. |

| 1634 | Maryland is founded as a refuge for English Catholics. |

| 1636 | Rhode Island is settled by Roger Williams, who seeks religious freedom. |

| 1638 | New Sweden is established in present-day Delaware by Swedish settlers. |

| 1664 | The English capture New Amsterdam (later renamed New York) from the Dutch. |

| 1681 | Pennsylvania is founded by William Penn as a haven for Quakers. |

| 1691 | The Massachusetts Bay Colony is merged with Plymouth Colony and other territories to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay. |

| 1712 | North Carolina separates from the Province of Carolina and becomes a separate colony. |

| 1713 | The Treaty of Utrecht ends Queen Anne’s War and transfers Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) from France to Great Britain. |

| 1732 | Georgia is founded as a colony for debtors and as a buffer between South Carolina and Spanish Florida. |

| 1754-1763 | The French and Indian War takes place, involving the British and French with their Native American allies. |

| 1765 | The Stamp Act is imposed on the colonies, leading to widespread protests and boycotts. |

| 1770 | The Boston Massacre occurs when British soldiers fire into a crowd of colonists, killing five people. |

| 1773 | The Boston Tea Party takes place, where colonists dump tea into Boston Harbor to protest the Tea Act. |

| 1774 | The First Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia to discuss grievances against British policies. |

| 1775 | The Battles of Lexington and Concord mark the beginning of the American Revolution. |

| 1776 | The Declaration of Independence is adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, declaring the colonies’ independence from Great Britain. |

| 1783 | The Treaty of Paris is signed, officially ending the American Revolution and recognizing the United States as an independent nation. |

Below is a more detailed discussion of each of the above events in the 13 colonies and the evolution of colonial America

Timeline of Colonial America

1607 – Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America, is founded in Virginia

In 1607, Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America, was founded in Virginia. This momentous event marked the beginning of a new chapter in history, as English colonists embarked on a bold venture to establish a thriving community across the Atlantic.

Sponsored by the Virginia Company of London, a joint-stock company seeking profits from colonization, a group of approximately 100 settlers set sail from England in December 1606.

Also Read: Timeline of the Jamestown Colony

After a treacherous voyage lasting several months, the expedition arrived at the Chesapeake Bay in April 1607. The settlers, led by Captain Christopher Newport, explored the area before selecting a site along the James River as the location for their settlement.

The spot was strategically chosen for its defensibility, access to water for trade and transportation, and potential for agricultural development.

Life in Jamestown during the early years was exceedingly difficult. The colonists faced a myriad of hardships, including outbreaks of disease, scarce food supplies, and strained relations with the Native American tribes, particularly the powerful Powhatan Confederacy.

Despite the adversity, the colonists persevered. They constructed fortifications to protect themselves and established a governing body known as the Virginia House of Burgesses. Additionally, they implemented agricultural practices, with tobacco emerging as a significant cash crop that would shape the colony’s economy and future development.

1620 – The Pilgrims establish Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts

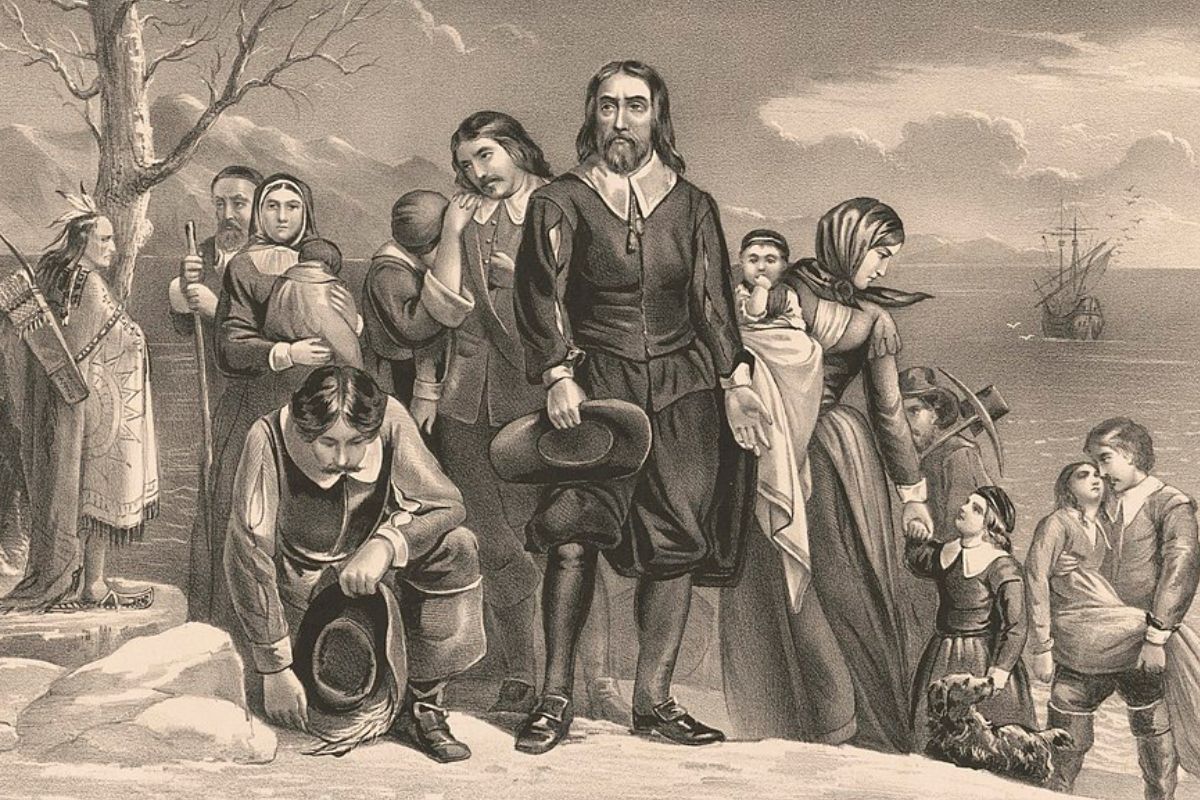

In 1620, the Pilgrims, a group of English Separatists seeking religious freedom, established Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts. Fleeing religious persecution in England, they embarked on a perilous journey aboard the ship Mayflower.

The Pilgrims initially intended to settle in Virginia, where they had received permission from the Virginia Company. However, due to storms and navigational challenges, they ended up landing far north of their intended destination, in an area known as Cape Cod. Realizing they were outside the jurisdiction of the Virginia Company, they decided to establish their own self-governing colony.

On December 21, 1620, the Pilgrims, led by their governor William Bradford, set foot on Plymouth Rock. They faced a harsh winter with limited resources and harsh conditions, which resulted in the loss of many lives.

However, with the help of Native Americans, particularly Squanto and the Wampanoag tribe, the Pilgrims learned to cultivate the land, hunt, and fish, which ultimately ensured their survival.

The following year, in 1621, the Pilgrims celebrated the first Thanksgiving, a harvest festival where they expressed gratitude for their bountiful harvest and the support they received from the Native Americans.

Plymouth Colony operated under the Mayflower Compact, a governing document that established guidelines for self-government and majority rule. The Pilgrims established a democratic system, where adult male colonists could participate in town meetings and contribute to decision-making.

Despite the challenges, Plymouth Colony thrived and attracted new settlers over time. It became known for its focus on agriculture, trade, and religious freedom.

1630 – The Massachusetts Bay Colony is established by Puritan settlers, with Boston as its capital

In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established by Puritan settlers in the New England region of North America. Led by John Winthrop, the colonists sought to create a religiously pure society based on their interpretation of Protestant Christianity.

The settlers arrived aboard a fleet of ships known as the Winthrop Fleet and settled in the area around present-day Boston. They established their capital in Boston and began building communities throughout the region.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony differed from earlier settlements like Plymouth Colony in that it was not founded for religious separatism but rather for the purpose of creating a unified Puritan society.

Under the leadership of John Winthrop, the Massachusetts Bay Colony implemented a theocratic form of government. The Puritan leaders sought to create a society based on strict moral and religious principles, enforcing a code of conduct rooted in their interpretation of biblical teachings.

The colony placed great importance on education and established Harvard College (now Harvard University) in 1636, the first institution of higher learning in British North America.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony grew rapidly as more Puritans migrated to the region, seeking religious freedom and the opportunity to live in accordance with their beliefs.

The colony established additional towns and settlements, such as Salem and Charlestown, which played important roles in the economic and political development of the region.

1634 – Maryland is founded as a refuge for English Catholics

In 1634, Maryland was founded as a refuge for English Catholics in the New World. The colony was established under the leadership of Lord Baltimore, whose original name was George Calvert but later passed to his son Cecilius Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore.

George Calvert, a prominent English nobleman and convert to Catholicism, sought a safe haven for Catholics who faced persecution and discrimination in England. He envisioned Maryland as a place where individuals of all Christian denominations, including Catholics, could practice their faith freely.

The first settlement in Maryland was St. Mary’s City, located on the banks of the Potomac River. Lord Baltimore granted settlers large tracts of land to encourage immigration and create a diverse and prosperous colony. The proprietary system of governance allowed Lord Baltimore and his descendants to act as the colony’s rulers, granting religious freedom and encouraging economic development.

The religious tolerance established in Maryland attracted not only English Catholics but also Protestants seeking freedom of worship. This inclusive policy helped promote the growth of the colony, attracting settlers from various backgrounds and faiths.

However, despite the vision of religious harmony, tensions emerged between the Catholic minority and the growing Protestant population. Protestant settlers outnumbered Catholics, and political struggles occasionally arose.

In 1649, the Maryland Toleration Act was passed, guaranteeing religious freedom to all Christians, but it was later repealed during a Protestant revolt in the 1650s.

In 1692, after the Glorious Revolution in England, the Protestant majority gained control of the Maryland government, and the Church of England became the official church. Catholics faced renewed restrictions and discrimination, although some degree of religious tolerance remained.

1636 – Rhode Island is settled by Roger Williams, who seeks religious freedom

In 1636, Rhode Island was settled by Roger Williams, a prominent religious leader who sought religious freedom. Williams, a Puritan minister, had faced persecution and conflict with the authorities in the Massachusetts Bay Colony due to his unconventional religious beliefs and his criticism of the colony’s close ties between church and state.

Driven by his desire for religious liberty and the separation of church and state, Williams ventured into the wilderness and established a settlement in what is now present-day Providence, Rhode Island.

He named the settlement “Providence Plantations” and envisioned it as a place where individuals could freely practice their faith without interference from the government.

Williams welcomed people of various religious backgrounds to his settlement, including those who were persecuted for their beliefs. He advocated for the fair treatment of Native Americans, forming positive relationships with local tribes and acquiring land through fair negotiations.

Rhode Island quickly became known as a bastion of religious freedom and tolerance. The colony’s government, established under Williams’ guidance, was among the first in the New World to fully separate church and state, ensuring that individuals had the right to practice any religion or no religion at all.

This commitment to religious liberty attracted individuals from different faiths and played a significant role in the colony’s growth and diversity.

In 1644, Williams obtained a royal charter from England, officially establishing Rhode Island as a separate colony. The charter reinforced the colony’s commitment to religious freedom and allowed for self-governance.

Additionally, Rhode Island’s colonial charter served as a model for religious liberty provisions in later American colonial charters and, eventually, the United States Constitution.

1638 – New Sweden is established in present-day Delaware by Swedish settlers

In 1638, New Sweden was established in present-day Delaware by Swedish settlers. The colony was part of Sweden’s efforts to expand its influence and establish a foothold in the New World.

Under the leadership of Peter Minuit, who had previously served as the director-general of New Netherland (present-day New York), Swedish colonists arrived in the Delaware Valley. They established the main settlement of Fort Christina, named after Sweden’s child queen, in what is now Wilmington, Delaware.

The Swedish settlers sought to engage in profitable trade with the Native American tribes and exploit the region’s abundant natural resources, such as furs, timber, and tobacco. They developed friendly relations with some of the local tribes, particularly the Lenape, fostering trade partnerships and alliances.

New Sweden faced competition and territorial disputes with neighboring European colonies, particularly the Dutch colony of New Netherland to the north and the English colonies to the south. Conflicts over land ownership and trade routes frequently arose, leading to tensions and occasional armed clashes.

In 1655, the Dutch, under the leadership of Peter Stuyvesant, launched a military campaign against New Sweden, eventually capturing Fort Christina and incorporating the territory into New Netherland. The English later wrested control of the region from the Dutch, leading to the eventual English domination of the entire Mid-Atlantic region.

While New Sweden’s existence as a distinct colonial entity was relatively short-lived, lasting less than two decades, its impact on the region was significant. The Swedish settlers brought their own cultural traditions, agricultural practices, and architectural styles, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of the Delaware Valley.

1664 – The English capture New Amsterdam (later renamed New York) from the Dutch

In 1664, the English captured New Amsterdam, a Dutch settlement located in present-day Manhattan, New York City. The capture of New Amsterdam marked a significant event in the ongoing conflicts between England and the Dutch Republic for control over valuable trading territories in North America.

At the time, New Amsterdam was a thriving trading outpost and the capital of New Netherland, a Dutch colony in the region. The English, seeking to expand their influence and secure control over profitable trade routes, dispatched a fleet led by Colonel Richard Nicolls to challenge Dutch dominance.

Under the threat of a military assault, the Dutch governor of New Netherland, Peter Stuyvesant, surrendered the colony to the English without engaging in open warfare. The English subsequently renamed the city and colony “New York” in honor of James, Duke of York, who later became King James II of England.

Also Read: Timeline of the New York Colony

The change in control had a profound impact on the region. The English implemented their legal and administrative systems, replacing Dutch institutions. They also encouraged English settlement, leading to an influx of English colonists who brought their own cultural, social, and political practices to the region.

While the Dutch influence waned, elements of Dutch heritage persisted in the newly renamed New York. The Dutch legacy can be seen in the names of certain neighborhoods, streets, and landmarks, as well as in the architectural styles that reflect Dutch colonial influences.

The capture of New Amsterdam by the English was a pivotal moment in the colonization of North America, as it firmly established English dominance in the region. New York would go on to become a key economic and cultural center, shaped by waves of immigration and the diverse influences of various ethnic groups.

1681 – Pennsylvania is founded by William Penn as a haven for Quakers

In 1681, Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn as a haven for Quakers, a religious group facing persecution in England. Penn, a prominent Quaker and the son of Admiral Sir William Penn, received a royal charter from King Charles II to establish the colony.

Penn envisioned Pennsylvania as a place where Quakers and other religious dissenters could freely practice their faith without fear of persecution. He sought to create a society based on principles of religious freedom, equality, and peaceful coexistence.

Penn’s colony attracted Quakers from England, as well as other religious groups seeking religious liberty, including Mennonites, Amish, and Baptists. The colony quickly became known for its commitment to religious tolerance, welcoming settlers of various faiths.

Under Penn’s guidance, Pennsylvania implemented a unique governmental structure. The Frame of Government, also known as the Charter of Liberties, served as Pennsylvania’s constitution and emphasized democratic principles, including popular representation and the separation of powers.

Pennsylvania’s capital, Philadelphia, became a vibrant and cosmopolitan city, known for its commitment to religious freedom, intellectual pursuits, and economic opportunities. Philadelphia attracted a diverse population and became a center for commerce and trade.

Pennsylvania’s relationship with Native American tribes was also notable. Penn believed in fair and peaceful relations with the indigenous peoples and sought to establish treaties and purchase land directly from them.

1691 – The Massachusetts Bay Colony is merged with Plymouth Colony and other territories to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay

In 1691, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was merged with Plymouth Colony and other territories to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay. This merger was part of a larger effort by the English Crown to exert greater control over the New England colonies and streamline colonial administration.

Prior to the merger, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had established itself as a thriving Puritan settlement, known for its strong religious convictions and self-governing institutions. Meanwhile, Plymouth Colony, founded by the Pilgrims in 1620, had its own distinct history and form of governance.

In 1685, King James II sought to consolidate control over the New England colonies and revoke their separate charters. He aimed to replace their self-governing structures with a more centralized and direct rule from England. This led to the revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter in 1684.

In 1691, a new royal charter was granted to the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which encompassed the territories of the former Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, and other nearby areas. The merger brought the two colonies together under a unified government, subject to greater oversight and control by the English Crown.

The Province of Massachusetts Bay continued to operate under a representative government, with an elected General Court that served as the legislative body. However, the English monarch appointed the governor, and certain decisions and policies required approval from the Crown.

The merger of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plymouth Colony into the Province of Massachusetts Bay marked a significant shift in colonial governance.

While the individual colonies had enjoyed varying degrees of self-governance, the formation of the province resulted in increased royal control and greater uniformity in colonial administration.

The Province of Massachusetts Bay would go on to play a pivotal role in American history, serving as a hotbed of revolutionary sentiment and contributing to the eventual fight for American independence.

1712 – North Carolina separates from the Province of Carolina and becomes a separate colony

In 1712, North Carolina officially separated from the larger Province of Carolina and became a distinct and separate colony. The division occurred due to political and geographical differences between the northern and southern regions of Carolina.

The Province of Carolina had been established in 1663 when King Charles II of England granted a charter to a group of eight English nobles known as the Lords Proprietors. The Lords Proprietors held authority over the entire region, which included present-day North Carolina and South Carolina.

Over time, tensions and conflicts arose between the settlers in the northern and southern parts of Carolina. The northern region, which encompassed areas such as Albemarle Sound and the Outer Banks, had developed its own distinct economy and political structure. Many settlers in the north were small farmers, traders, and fishermen.

In 1712, due to disagreements and dissatisfaction with the rule of the Lords Proprietors, the settlers in the northern region successfully petitioned the crown to separate and establish their own colonial government. The northern part of Carolina officially became the separate colony of North Carolina.

The separation of North Carolina from the Province of Carolina allowed the colony to pursue its own political and economic interests. It developed its own legislative body, the General Assembly, which represented the interests of the North Carolina settlers.

The colony continued to grow and attract immigrants from various backgrounds, including English, Scottish, Irish, and German settlers.

North Carolina’s economy primarily relied on agriculture, with tobacco being a major cash crop. The colony also had a significant naval stores industry, producing tar, pitch, and turpentine from the vast pine forests.

The separation of North Carolina from the Province of Carolina marked a significant step towards establishing an independent colonial identity. It allowed the settlers in North Carolina to have greater control over their own affairs and pursue their own economic interests.

1713 – The Treaty of Utrecht ends Queen Anne’s War and transfers Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) from France to Great Britain

In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht was signed, marking the end of Queen Anne’s War, a conflict between Great Britain and France over territorial disputes in North America.

The treaty resulted in several significant territorial changes, including the transfer of Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) from France to Great Britain.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht, France ceded Acadia and its surrounding areas, including Newfoundland, to Great Britain. This transfer of territory reflected the shifting balance of power between the European colonial powers and had lasting implications for the region.

The British took control of Acadia and established their authority over the newly acquired territory. However, the treaty did not clearly define the borders of Acadia, leading to ongoing disputes and conflicts between the British and the French-speaking Acadians, who had settled in the region.

Over the following decades, tensions between the Acadians and the British colonial authorities escalated. The British sought to exert greater control over the Acadian population, including imposing loyalty oaths and other measures.

This culminated in the Expulsion of the Acadians in 1755, when thousands of Acadians were forcibly removed from their homes and dispersed throughout the British colonies.

The Treaty of Utrecht and the transfer of Acadia to British control had long-lasting consequences for the region. It contributed to the emergence of Nova Scotia as a British colony and shaped the subsequent development of the area.

The treaty also set the stage for future conflicts between France and Britain in North America, most notably the French and Indian War, which ultimately led to the British gaining control over much of New France (present-day Canada) in 1763.

1732 – Georgia is founded as a colony for debtors and as a buffer between South Carolina and Spanish Florida

In 1732, Georgia was founded as a colony by a charter granted to James Oglethorpe and the Trustees for the Establishment of the Colony of Georgia in America. The establishment of Georgia served two primary purposes: as a refuge for debtors and as a buffer between the British colony of South Carolina and Spanish Florida.

One of the main objectives behind Georgia’s founding was to provide a fresh start for debtors in England. Oglethorpe and the Trustees aimed to create a colony where debtors, who often faced imprisonment and harsh conditions, could have an opportunity to rebuild their lives.

By offering them a chance to settle in a new land, the Trustees hoped to alleviate social and economic issues back in England.

The other purpose of Georgia’s establishment was to serve as a buffer between the British colony of South Carolina and Spanish Florida, which was still under Spanish control at the time.

The proximity of Spanish Florida raised concerns for the British as they sought to protect South Carolina’s borders from potential Spanish invasions and influence.

Georgia was seen as a defensive outpost that could act as a barrier and provide an additional layer of security for the British colonies.

To ensure the success of the colony, the Trustees implemented a set of regulations and guidelines for the settlers. These included restrictions on land ownership, prohibition of slavery, and limitations on trade.

The intention was to create an egalitarian society and prevent the concentration of wealth and power. The Trustees also had the goal of maintaining friendly relations with the Native American tribes in the region, promoting peaceful coexistence.

Over time, however, the original vision for Georgia shifted. Economic challenges, conflicts with Native American tribes, and the desire for greater economic growth led to changes in policies.

Restrictions on land ownership were lifted, slavery was introduced, and plantation agriculture, particularly the cultivation of crops like rice and indigo, became important economic activities.

1754-1763 – The French and Indian War takes place, involving the British and French with their Native American allies

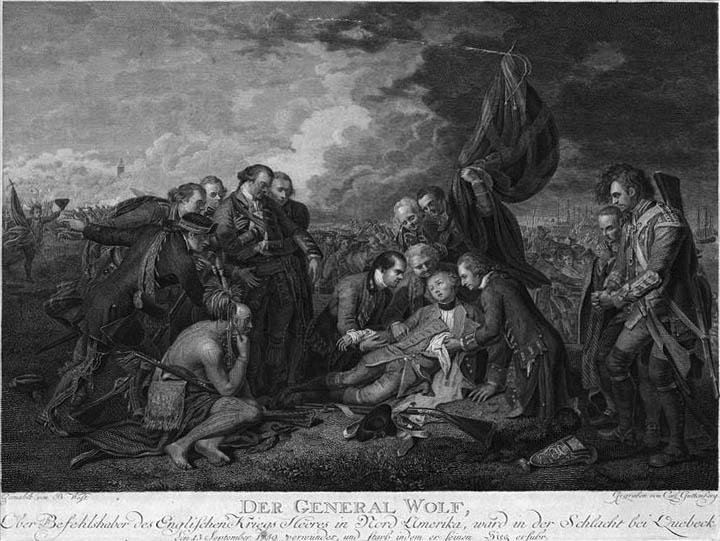

From 1754 to 1763, the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years’ War, took place. It was a conflict between the British and the French, with their respective Native American allies, over territorial disputes in North America.

The war began in the Ohio River Valley, where both the British and the French sought control over lucrative fur trade networks and territorial expansion. The conflict quickly escalated, drawing in Native American tribes aligned with either side.

The French and their Native American allies initially achieved several military successes, particularly in the early years of the war. They had well-established alliances with various indigenous nations, which provided them with valuable support in the form of supplies, knowledge of the terrain, and guerilla warfare tactics.

However, the tide of the war turned in favor of the British as the conflict progressed. The British forces, led by figures like General Edward Braddock and later General Jeffrey Amherst, adopted more effective strategies and received reinforcements from Britain.

The British navy also played a crucial role in blockading French supply lines and cutting off their access to crucial resources.

The turning point came in 1759 when the British won significant victories, such as the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and the decisive Battle of Quebec under the leadership of General James Wolfe. The following year, in 1760, the British captured Montreal, effectively ending French control over Canada.

The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763, officially ended the French and Indian War. Under the treaty, France ceded its North American territories to the British. This included Canada and all French claims east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans and a few small islands in the Caribbean.

Although the British emerged victorious, the war left Britain heavily indebted. The cost of maintaining military forces in North America and funding the war effort had strained the British economy.

In response to the financial burden, the British government sought to impose various taxes and regulations on the American colonies, which ultimately contributed to growing tensions and resentment leading to the American Revolution.

1765 – The Stamp Act is imposed on the colonies, leading to widespread protests and boycotts

In 1765, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a law that imposed taxes on a wide range of printed materials in the American colonies. This act, intended to generate revenue for the British government, sparked significant opposition and played a pivotal role in fueling the growing tensions between Britain and its American colonies.

The Stamp Act required that various documents, including legal papers, newspapers, pamphlets, and playing cards, carry an official government stamp, which could only be obtained by paying a tax.

This tax was seen as a direct violation of the principle of “no taxation without representation,” as the American colonists had no elected representatives in the British Parliament who could vote on such matters.

The Stamp Act met with immediate resistance and outrage from the colonists. They viewed it as an infringement on their rights, economic hardship, and an encroachment on their self-governance. Widespread protests erupted throughout the colonies, with organized boycotts, demonstrations, and acts of civil disobedience.

Groups such as the Sons of Liberty emerged as vocal opponents of the Stamp Act, leading public demonstrations and organizing boycotts of British goods. The colonial response to the act brought together people from various social and economic backgrounds, fostering a sense of unity in opposition to British policies.

In addition to the popular protests, colonial legislatures took action against the Stamp Act. The Virginia House of Burgesses passed the Virginia Resolves, asserting that only the colonial assembly had the authority to tax the colonists. Similar resolutions were passed in other colonies, demonstrating a unified resistance against the act.

The colonial opposition had a significant impact on British policy. Merchants in Britain, facing the loss of American markets due to colonial boycotts, exerted pressure on Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act.

In 1766, the British government, recognizing the economic and political consequences of the act, repealed it, marking a significant victory for the colonists.

While the Stamp Act itself was short-lived, its legacy was far-reaching. The resistance it sparked contributed to the broader movement for American independence and set a precedent for future opposition to British policies.

1770 – The Boston Massacre occurs when British soldiers fire into a crowd of colonists, killing five people

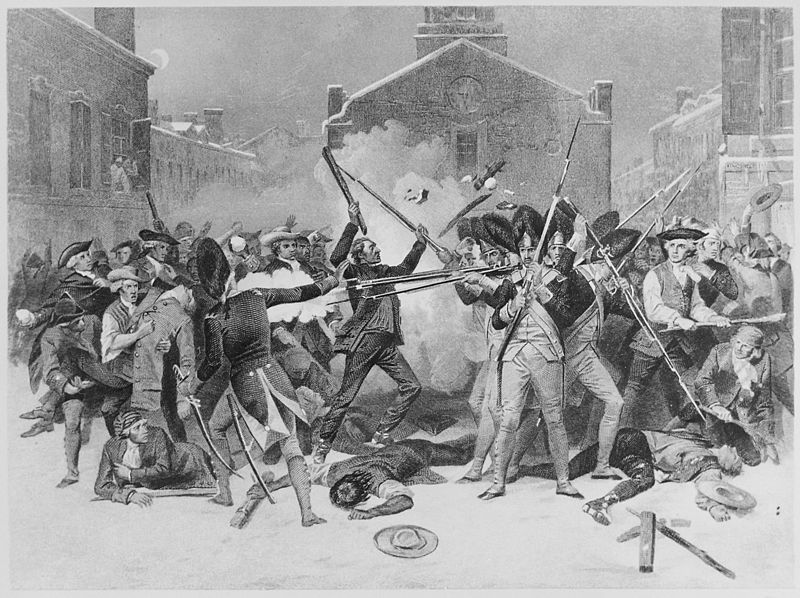

In 1770, the Boston Massacre took place, an event that marked a significant escalation of tensions between British soldiers and the American colonists in Boston. The incident unfolded when a confrontation between colonists and British soldiers erupted into violence, resulting in the deaths of five colonists.

The Boston Massacre occurred against the backdrop of growing resentment and animosity towards British authorities in the American colonies. The presence of British troops, stationed in Boston to enforce British policies and maintain order, had long been a source of tension and friction with the local population.

On the evening of March 5, a group of colonists began taunting and provoking a small contingent of British soldiers near the Custom House on King Street (now State Street) in Boston. The soldiers, outnumbered and facing hostility, found themselves surrounded by an angry mob of colonists.

In the chaos that ensued, the soldiers, feeling threatened and fearing for their safety, opened fire into the crowd. As a result, three colonists, including Crispus Attucks, a Black man, were killed instantly, and two others died later from their injuries. Several other colonists were injured in the incident.

News of the Boston Massacre spread rapidly, causing outrage and further inflaming anti-British sentiment among the colonists. The incident became a focal point of colonial propaganda, with portrayals of British soldiers as oppressive and brutal oppressors.

The aftermath of the Boston Massacre saw legal proceedings against the British soldiers involved. Defended by future U.S. President John Adams, some soldiers were acquitted, while others were found guilty of lesser charges.

The Boston Massacre played a significant role in galvanizing colonial opposition to British rule. It further deepened the sense of grievance and the desire for self-governance among the American colonists.

The event fueled calls for greater unity and resistance against British authority, ultimately contributing to the momentum leading up to the American Revolution.

1773 – The Boston Tea Party takes place, where colonists dump tea into Boston Harbor to protest the Tea Act

In 1773, the Boston Tea Party occurred, one of the most iconic acts of resistance by American colonists against British taxation policies.

It was a direct response to the Tea Act passed by the British Parliament, which granted a monopoly to the East India Company and imposed taxes on tea imported into the American colonies.

The Tea Act aimed to rescue the financially struggling East India Company by granting it exclusive rights to sell tea directly to the American colonies. This move would bypass colonial merchants and potentially lower the price of tea, but it also maintained the principle of taxation without colonial representation.

In protest of the Tea Act and the violation of their rights, a group of colonists, known as the Sons of Liberty, organized the Boston Tea Party. On the night of December 16, disguised as Native Americans, a group of men boarded three British tea ships docked at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston Harbor.

The participants, led by Samuel Adams and others, proceeded to dump approximately 342 chests of tea into the harbor. This symbolic act of defiance demonstrated the colonists’ refusal to accept British taxation policies without their consent and their determination to resist what they considered unfair and oppressive measures.

The Boston Tea Party elicited strong reactions from both sides. The British government responded with outrage and vowed to punish the participants.

In retaliation, the British Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, which included the closing of the port of Boston, restricting colonial self-government, and quartering British soldiers in private homes.

The Boston Tea Party and the subsequent Coercive Acts further united the American colonies against British rule. It sparked solidarity among the colonists, with other ports refusing to unload East India Company tea shipments and staging their own acts of resistance.

The event played a pivotal role in shaping the path toward the American Revolution. It fueled anti-British sentiments, strengthened colonial opposition, and brought issues of representation and taxation to the forefront.

1774 – The First Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia to discuss grievances against British policies

In 1774, the First Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This historic meeting brought together delegates from twelve of the thirteen American colonies to address their grievances against British policies and to discuss potential responses to the escalating tensions with Great Britain.

The primary catalyst for convening the First Continental Congress was the passage of the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, by the British Parliament in response to the Boston Tea Party.

The Coercive Acts aimed to punish Massachusetts for its role in the Tea Party by closing the port of Boston, curbing self-governance, and imposing stricter British control.

Delegates from all participating colonies, except for Georgia, were chosen to represent their respective colonial legislatures. Prominent figures such as George Washington, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry were among those in attendance.

The delegates convened to discuss a range of grievances and issues, including the violation of colonial rights, taxation without representation, and the infringement on self-governance. They sought to establish a unified response and coordinate actions to address these concerns.

During the congress, the delegates engaged in spirited debates and discussions, sharing their perspectives on the challenges facing the colonies and proposing potential courses of action.

The congress adopted the Suffolk Resolves, which supported the people of Massachusetts in their resistance against the Coercive Acts and called for the colonies to organize militias for self-defense.

The congress also issued a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which asserted the colonists’ rights as Englishmen and denounced the violation of those rights by the British government. The declaration outlined the colonists’ objections to specific acts of Parliament and urged the king to address their concerns and restore harmony between Britain and the colonies.

While the First Continental Congress fell short of advocating for independence from Great Britain, it laid the foundation for future resistance and the eventual call for independence.

1775 – The Battles of Lexington and Concord mark the beginning of the American Revolution

In 1775, the Battles of Lexington and Concord took place, marking a significant turning point in the American Revolution and the beginning of armed conflict between the American colonists and British forces.

Tensions between the colonists and the British had been escalating for years, with disputes over taxation, representation, and colonial self-governance. The conflict came to a head when British troops were ordered to seize colonial military supplies and arrest rebel leaders in the town of Concord, Massachusetts.

On the morning of April 19, British soldiers marched from Boston towards Concord. However, the colonial militias had received advance warning of the British movements through a network of riders, including Paul Revere and William Dawes. As a result, colonial militia members, known as Minutemen, gathered in Lexington to confront the approaching British troops.

The first shots of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington Green, where the British and colonial forces clashed. Though the encounter was brief, it resulted in several colonial casualties, marking the beginning of open hostilities.

The British troops continued their march to Concord, but by that time, the colonial militias had mobilized and prepared for defense. At the North Bridge in Concord, the two sides engaged in a more significant battle, with the colonial forces successfully driving back the British soldiers.

As the British troops retreated to Boston, they faced continuous harassment from colonial militiamen along the way. The engagements at Lexington and Concord demonstrated the determination and willingness of the American colonists to fight for their rights and resist British oppression.

News of the battles spread quickly throughout the colonies, rallying more colonists to join the cause of independence. The conflicts at Lexington and Concord galvanized colonial sentiment and set in motion the events that would lead to the American Revolutionary War.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were significant because they represented the first military engagements of the American Revolution. They marked a definitive shift from peaceful protest to armed resistance against British rule.

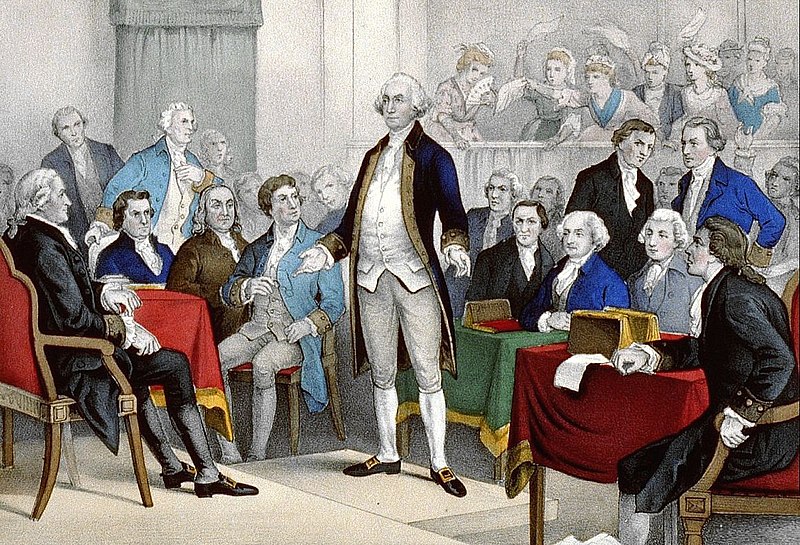

1776 – The Declaration of Independence is adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, declaring the colonies’ independence from Great Britain

In 1776, on July 4th, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, a momentous document that declared the American colonies’ independence from Great Britain.

The adoption of the Declaration marked a pivotal moment in American history and laid the foundation for the establishment of the United States of America as an independent nation.

The Declaration of Independence was primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson, with contributions and revisions from other members of the drafting committee, including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin.

The document served as a formal proclamation to the world, explaining the colonists’ reasons for breaking away from British rule and asserting their right to self-governance.

The Declaration of Independence began with a powerful opening statement that has become iconic: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

It articulated the fundamental principles of human rights and individual liberties that underpin the American ideals of freedom and equality.

The document then detailed a list of grievances against King George III and the British government, highlighting the ways in which the colonists’ rights had been violated and their pleas for redress ignored. The Declaration emphasized the inherent right of the people to alter or abolish oppressive governments and establish new systems that protect their rights and liberties.

By adopting the Declaration of Independence, the Second Continental Congress not only declared the colonies’ separation from Great Britain but also proclaimed the birth of a new nation based on principles of self-determination, popular sovereignty, and the protection of individual rights.

The Declaration served as an assertion of the colonists’ unity, resolve, and their commitment to the cause of independence.

The Declaration of Independence had profound consequences. It inspired and rallied colonists across the thirteen colonies to support the revolutionary cause and fight for their freedom. It also played a significant role in gaining international support for the American Revolution, as other nations began to view the colonists’ struggle as a legitimate fight for liberty against tyranny.

1783 – The Treaty of Paris is signed, officially ending the American Revolution and recognizing the United States as an independent nation

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed, bringing an end to the American Revolution and officially recognizing the United States as an independent nation.

The treaty was negotiated between the United States and Great Britain, with representatives from both sides working to establish the terms of peace and outline the boundaries and rights of the newly formed nation.

The Treaty of Paris recognized the United States as a sovereign and independent country, separate from British rule. It acknowledged the legitimacy of the American colonies’ claims to self-governance and confirmed their right to establish their own government, laws, and institutions.

The signing of the Treaty of Paris marked the formal conclusion of the American Revolution and the successful achievement of American independence. It established the United States as a recognized nation on the world stage, opening the door to diplomatic relations and trade agreements with other countries.

The treaty had a significant impact not only on the United States but also on global politics. It signaled a shift in the balance of power and dealt a blow to Great Britain’s imperial aspirations in North America. It also inspired other nations around the world to pursue their own quests for independence and self-determination.